I have just seen a series of photographs on Instagram that made my blood boil. Currently, we are in the midst of game season, and I believe we should utilise this wonderful product to its fullest potential. I hold a deep passion for this topic, having been an avid shooter and authoring a game cookbook. While it is great to see fresh game being used in season and promoting its use too, which I applaud, please, I beg of you, if you are trying to promote its use, then, like anything else, do it well or don’t bother doing it at all.

If you are going to effectively “show off”, that is, use photographs of your work to show how good it is and how appetising and tasty it is and make it a reason for people to come and try your food, then try showing something properly done; show it at its best, and where food is concerned, then surely it should be appetising at the very least.

The list of issues regarding the preparation, cooking, and serving of these magnificent birds in the photographs includes numerous mistakes, poor practices, and substandard workmanship.

Cooking is an art that requires love, respect, and understanding of food in all its forms; without these, you can’t be a good cook, let alone a chef. The term ‘cooking’ is not limited to the application of heat to raw foods. It applies to all aspects, from purchasing it to its preparation, through the actual cooking, and finally to serving.

Preparing a game bird for cooking is not for everyone; I get that, but the necessity to get it right remains, and if you are prepared to cook and eat it, then you should also be willing to do the proper preparation.

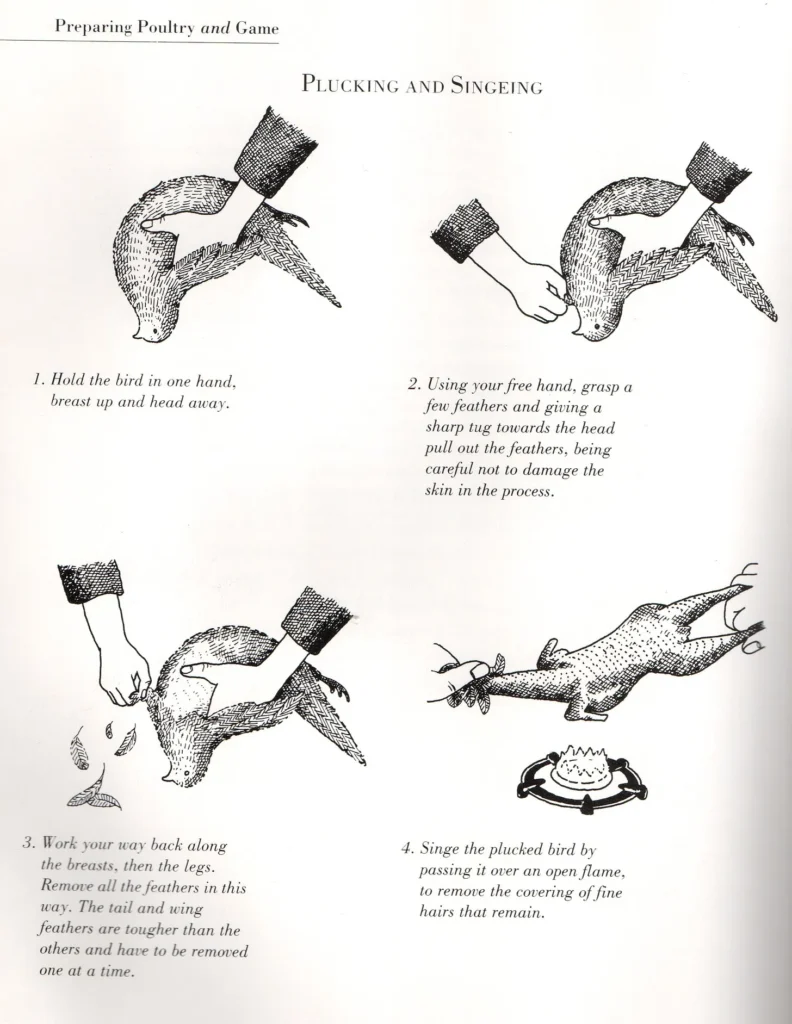

Let’s start with plucking, the removal of all the feathers prior to cooking. So many people just skin a game bird rather than going to the trouble of plucking it, especially pheasant. I can just about understand this in a domestic environment but not in a commercial chef-driven kitchen, surely. It needs to be plucked correctly and with care. Correctly so all the feathers are removed, even as far down as the knee joints and the parson’s nose. Carefully so as to avoid tearing the skin.

The bird should then be singed (in the attached photo it is clear that the birds have not been plucked completely or correctly, and the fine hairs can still be seen in the finished dish) to remove the fine hairs that cover the body that plucking and cooking will not remove.

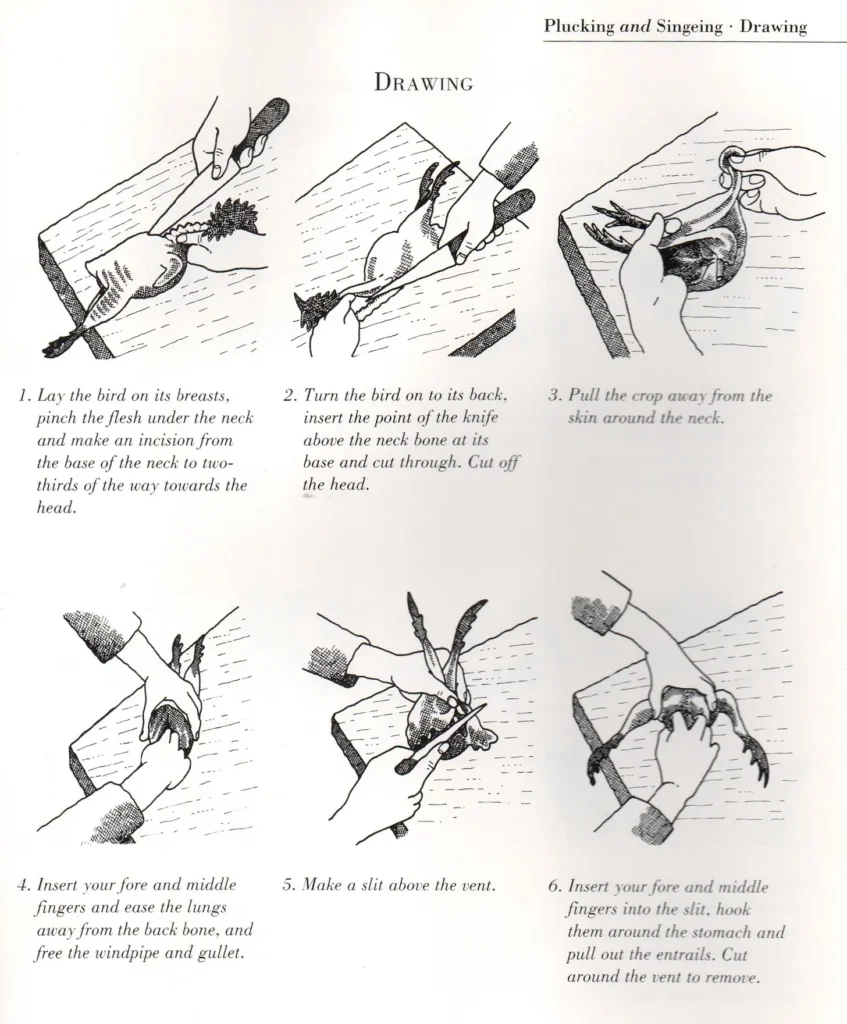

The feet should be cut off just above the ankle, not hacked off at the knee. To prepare the whole bird for roasting, the centre toe can and should be left on; only the two front toes and the rear one should be removed.

The neck should be cut as close to the body as possible, but the skin from the neck should be left and cut off just shy of the head. The entrails are then removed through a small incision just above the vent, having first loosened off the windpipe, crop and gullet from the skin of the neck and the lungs loosened from the back of the rib cage. For the best results the wishbone should be carefully removed before the bird is then trussed.

Let’s also appreciate that these birds had to die for someone to treat them like this, something that seems to be forgotten. If you’re a chef, then be proud and treat produce with respect, be it animal or vegetable; it matters not, it all deserves our respect. Is it too difficult, or do people just not care enough? Or is it that the students of today are being taught by those that actually know no better? If you don’t know how to do it, ask; I am happy to teach.

It has always been my mantra that it is easier to cook well than it is to cook badly, but it does not start there; it is far more satisfying to do the job well from the beginning, from choosing the product through storing it well and then preparing it as well as it can be. All this takes time, but it is so worth the effort.

Chef Ian McAndrew’s specialist eBooks and guides are available directly on ChefYesChef, including his technical titles and autobiography. If you want more practical, chef-led reading beyond this article, you’ll find the full collection here.

Chef Ian McAndrew works with chefs, businesses, and individuals on a wide range of culinary projects, from concept development to practical problem-solving.

If you’d like to talk through an idea or need informed guidance, you’re welcome to contact him.